Frame decisions as bets to improve decision making

This article covers:

An interesting way to think about making decisions is to consider each decision as a bet with yourself about future versions of your life.

Annie Duke who was a professional poker player winning high amounts of price money and big titles wrote a fascinating book called “Thinking in Bets” (You can buy it here).

I highly recommend reading it as she brings along a lot of fun and great examples, but if you want to get the gist of it, this post is for you.

Life is like poker, not chess

Her premise is that life is much more like poker than chess. Poker consists of a lot of uncertainty and luck in contrast to chess which has clear rules and is based purely on skill. Life just like poker depends on your decision making skill, but at the same time also brings along uncertainty and the need for luck.

In poker you need to make many decisions in a short amount of time, so she says that you should take the decision making lessons learned from poker to your other decisions in life.

Your life turns out based on the quality of your decisions and luck. Working out when it’s the one vs. the other is the goal to improve your decisions.

Humans form beliefs before checking them

When you make your decisions / place your bets, you do so based on your beliefs.

The trouble is that you often form your beliefs without checking them. You hear or read something and take it for granted. This has been shown in many psychology and neuroscience experiments. Humans are easy believers. This makes sense as in the past it was much more costly not to believe the things that were told to you by your parents / neighbors etc.

To further the trouble, not only do you easily build beliefs without vetting and checking them, you also defend them against new evidence, i.e. you select information which conforms with your previously established beliefs.

This makes sense from a cognitive bias perspective: you want to feel good and protect yourself against feeling bad, so if you have an established belief, it feels good to confirm it with new information and it feels bad to have information running against it as that would make you “wrong”.

Annie parts with the concept of being “right” or “wrong” and instead suggests to establish probabilities. So instead of saying “I know that Google stock will go up this week.” you say “I believe that Google stock will go up this week with 70% confidence”. Then when you encounter new evidence, e.g. Google presents their financials and they are worse than expected, you can correct your belief: “I believe that Google stock will go up this week with 30% confidence”. This feels better than saying: “I was wrong.” as it’s rather an update to your uncertainty.

This is considered hard, because using probabilities is like saying “I’m not sure” and we learn at school that saying that is a bad thing.

On the other hand, using uncertainty unlocks openness in discussions with others, because if we are not sure, others might be willing to jump in and let us know their opinion and together we can learn to come closer to the truth. In contrast, when you act like you are sure about a belief, then it’s harder for others to say something against it as they would imply that you are wrong which is socially awkward.

This is in particular also important in companies when making decisions together to keep this openness and avoid group think where the group just agrees to strongly voiced opinions.

Dangers of resulting

When thinking about our decisions, we most often look for the results to judge whether a decision was good or bad. If we see a good result, we think the decision was good. If we see a bad result, we think the decision was bad.

However, due to things beyond our control / uncertainty / luck this is not always the right way to look at our decisions.

In fact, good decisions can definitely lead to bad results and bad decisions to good results, because we get lucky.

Rather than looking at it this way, the typical mental bias humans employ is to refer good results to good decisions and bad results to luck / chance instead of a bad decision. That way you protect yourself from taking the blame of having taken a bad decision. This is called the “self-serving bias”.

And conversely, when looking at others, we frame bad outcomes to their bad decisions and good outcomes as luck :D

To learn the most about our decisions and improve on them, it’s important to break this mental bias.

Instead, we need to learn to figure out which decisions were good and which were bad. Of course, due to uncertainty, this is quite hard to do, because we can never be sure whether an outcome was due to our decision or other factors outside of our control.

The way to progress here is to also make bets on whether the outcome is due to skill or due to luck. If it’s likely due to skill, you can learn about the decision. If it’s likely due to luck, there is no learning opportunity.

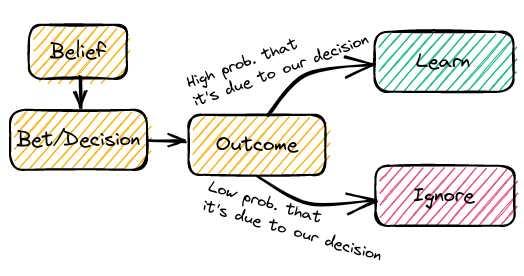

So the cycle looks like this:

Belief -> Bet / Decision -> Outcome -> Learn if high probability that it’s due to our decision / ignore if it’s due to chance

Wanna bet?

The cool thing about looking at decisions as bets is this: when you place money on a bet, you usually think very clearly about your beliefs and how likely you think they are and how sure you are about them. You would only take the bet if you are sure enough that you have a good chance to win it.

So the first thing that framing decisions as bets does is that you reconsider your beliefs more honestly and probabilistically.

But who are you betting against?

You are betting against all the future possible versions of your life, so basically against yourself, i.e. against all the paths you will not take.

So how to choose the future version of your life which is best for you?

That’s a trap, because due to uncertainty that’s not possible. You need to live with uncertainty and make the best decision given all the uncertainty.

When you make a big decision like whether to move to a new city, there is a lot at stake.

And there is also a lot of uncertainty! Of course, you don’t know what it will be like to live in that new city. You also don’t know how much you will miss your friends from the current city. And many more things. But given all your current beliefs, you can think about the future scenarios that could happen after making the decision and assign probabilities to them.

Then you make the decision with the better probabilistic overall outcome paths.

Changing your habits

So how to break the mental habit of framing your good results as good decisions and bad results as bad luck?

A habit consists of a cue (see the result) which triggers a routine (if result is good -> skill, if result is bad -> luck) which leads to a reward (I am awesome).

To change any habit, you need to keep the old cue and the old reward, but change the routine.

In this case you still need to feel good about yourself, so how to do that?

We can feel good about ourselves when we are a good credit-giver (praise someone for their good decision on a good outcome), a good mistake-admitter (admit a decision was not good on bad results), a good finder-of-mistakes-in-good-outcomes (figure out that an outcome was rather the result of luck and feel good about finding that out) and overall be a good learner and improve in our decision making.

It’s not easy and takes deliberate effort, but it’s worth it as improving our decisions has a compounding effect over time!

A good method to use is perspective taking: when we judge our own decisions / results, assume it was someone else and if we judge others decisions / results, assume it was our own.

I hope you enjoyed this book summary!

And if this is interesting and you want to dive deeper, get the book.

comments powered by Disqus